Exploring Singapore’s WW2 History: A Family Story

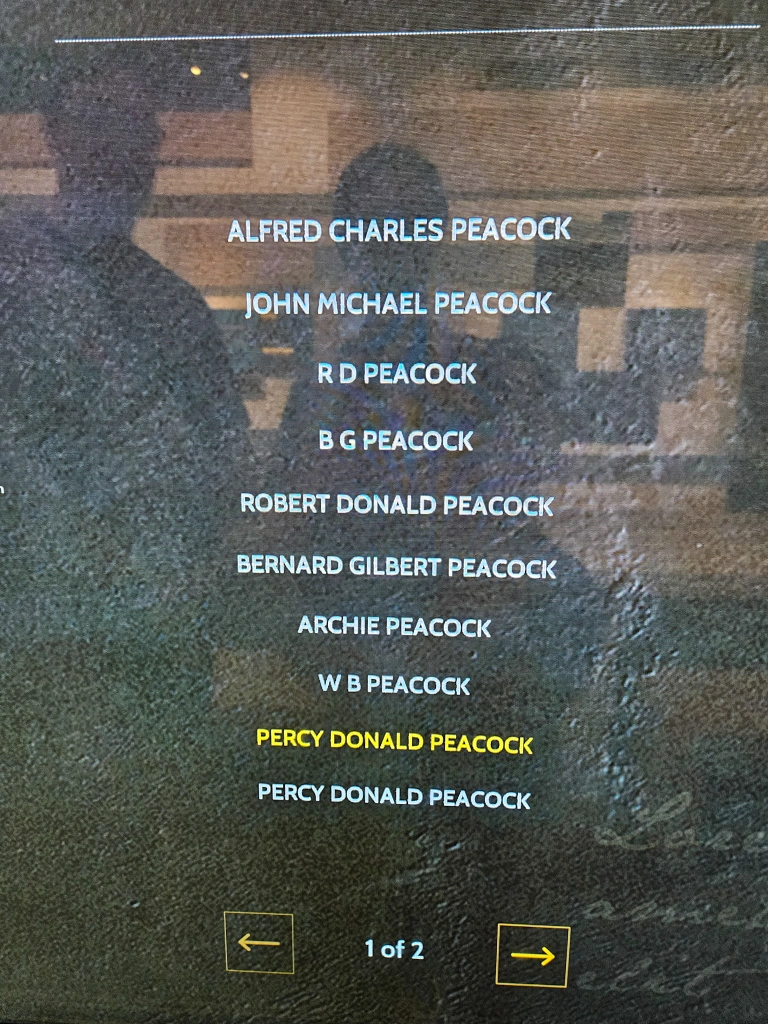

In memory of Percy Peacock.

During World War Two (WW2), Singapore was a British stronghold in South East Asia. In 1942, the Battle of Singapore saw the Japanese capture the city, leading to the largest British surrender in history. Singapore fell to the Japanese on Feb 15th 1942, and remained under Japanese occupation until 1945. During this time, atrocities were committed against both the captured soldiers and civilian population in Singapore.

My husband’s ancestor, Percy Peacock, fought in the Battle of Singapore, where he was captured and imprisoned – before being sent to Thailand to work on the construction of the Burma Railway. He never came home.

It was important to us to make sure we retraced his steps (and those of my great grandpa, more on him later) and beyond, across the country, to understand more of Singapore’s WW2 history.

WW2 Sites in Singapore

Changi Museum & Chapel

After the Japanese captured Singapore in 1942, they interred all the Allied (British, Australian etc) soldiers in a place called Changi, where they built a Prisoner of War (PoW) camp.

Changi Museum & Chapel remembers those interred in the PoW camp, tells their stories and gives a view as to what life was like here. The majority of soldiers captured were those who fought in the Battle of Singapore – mainly Australian and British soldiers. The British regiments stationed here at the time were mainly from Cambridgeshire and Norfolk.

Percy Peacock was in one of those Cambridgeshire regiments which fought in the Battle of Singapore and was captured. Percy, named after his mother’s brother who was captured as a German PoW in WW1, knew nothing other than home in the Cambridgeshire Fens. Percy married a local girl, Doris, on Christmas day before he was deployed. He had 4 siblings; Maurie, Marj, Len and Ron. These 4 people played a huge role in my mother in law’s upbringing, but she never met Percy and he wasn’t spoken about. She didn’t know his story.

Percy was captured in 1942 and kept at Changi for just over a year. I can’t imagine his fear as he was deprived of food, beaten, unable to send letters home, forced to sleep on concrete floors in cramped conditions, and afforded no freedom, before ultimately being sent to his death on the Burma Railway.

Whilst here, I like to think he found some comfort in a simple chapel the Prisoners built, or the small community they formed where music, reading and makeshift games were played. It was moving to discover the site, and pay tribute to Percy.

Before he was captured, Percy wrote to his mother Mabel (my husband’s great Grandma): “Dear Mother, Well we are off this time, Join the Army & see the world, well I certainly look as though I shall see some of it, I’ve always wanted to but not quite in this fashion“.

I wish he could have seen it through our eyes instead.

Civilian War Memorial

It’s now time to head to my great grandpa, Cyril Kenneth Sansbury, who served as Bishop of Singapore and Malaya post WW2 in the 1960s, during Colonial times. His obituary reads:

“In 1961 he was consecrated as the last expatriate Bishop of Singapore and Malaya. Sansbury, now 56, braved tedious travelling in the tropics and taught and preached with his customary skill and energy. Perhaps Archbishop Fisher, often ultra-cautious, would have been wiser to have chosen a young non-European for this very rapidly developing Asian diocese. A cathedral service in Singapore might use seven different languages. Sansbury felt keenly the ecclesiastical and political divisions imposed by history, European traders, colonial powers and missionaries…. and was glad to return to England.”

It was during this time, in 1963, 20 years after Percy’s death, that the Prime Minister at the time set aside a plot of land at Beach Road for the building of a memorial dedicated to the civilians killed in WW2. My great grandpa was on the construction committee and would have seen the memorial built.

The memorial is dedicated to the civilians, mainly many thousands of ethnic Chinese, who were killed in the Sook Ching Massacre and more. The civilian death toll was reported to be 6,000 by the Japanese, but official estimates range between 25,000 and 50,000.

Fort Canning Park & Battlebox

Fort Canning sits right at the heart of the Civic District in the city. It remained the headquarters of the British military operations until the outbreak of Second World War in 1941.

Notably, it is the location of The Battlebox, a bomb-proof command center, originally known as the Headquarters Malaya Command Operations Bunker. Built between 1936 and 1941, it served as a key operational hub for the Allied forces. It was here that Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival and other commanders made the decision to surrender Singapore to the invading Japanese forces in February 1942.

Kranji War Cemetery & Memorial

The Kranji War Memorial is located in northern Singapore, and pays tribute to the men and women from the UK, Australia, Malaya, India, Sri Lanka, Canada and New Zealand who died defending Singapore and Malaya against the invading Japanese during WW2.

The Cemetery houses 4,500 identified bodies with marked graves. The Memorial’s walls inscribe over 24,000 more names of Allied personnel whose bodies were never found, spread over both sides of 12 columns of the war memorial itself.

It is a sobering and moving sight.

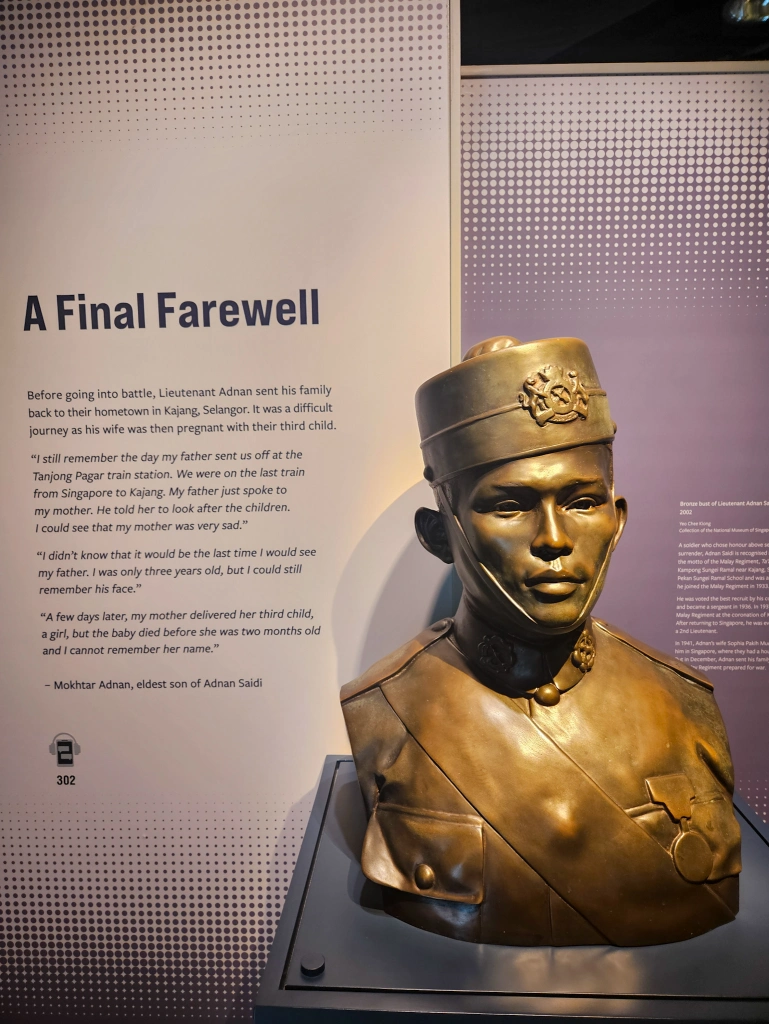

Reflections at Bukit Chandu

It wasn’t just the British and American soldiers who suffered horrendously at the hands of the Japanese. The Malayan Regiment, fighting as part of the British army, suffered significant casualties too. The Regiment is known for the stand it made at Bukit Chandu (literally translates at “Opium Hill” from Malay), which it held for as long as it could whilst being attacked by the Japanese. Every single person was slaughtered – apart from one. Abbas Abdul Manan somehow fought his way through the Japanese, crossed a 20ft wide drain filled with burning oil, and then rejoined the Battle of Singapore in another location!

The Regiment was lead by Lieutenant Adnan Saidi, an embodiment of the Regiment’s motto “Ta’at Setia” (faithful and true). He was a teacher before joining the Malay Regiment, where he was voted the best recruit and represented the Regiment at the coronation of King George VI in London. He died at Bukit Chandu along with around 150 others.

Fort Siloso

The fort was designed and built to defend Singapore against an invasion by sea from the south. However, during the Battle of Singapore, the guns were instead turned inland to fire at rapidly-advancing Japanese forces approaching from Malaya to the north. Ridiculously, in the confusion, a number of British and local troops were retreating south, but were mistaken for Japanese troops and fired upon, with at least major casualties sustained.

The building at the entrance of Fort Siloso is now known as the Surrender Chambers and has a vivid portrayal of the scenes of the British and Japanese surrenders in WWII with actual footage of the war being played.

Alexandra Hospital

In 1940, Alexandra Hospital was the best equipped British Military Hospital in the Far East, and it wasn’t spared during the Japanese invasion. The Japanese stormed the hospital on Saturday 14th Feb 1942. Despite hospital staff surrendering, the Japanese bayonetted many of them, including defenceless patients on operating tables and in hospital beds. Of over 200 staff and patients in the building at the time, only 5 lived to tell the story.

The hospital still exists and is still in use today.

Former Ford Factory

This is the site where Commander Arthur Percival surrendered to the Japanese on 15th February 1942, a day after the Alexandra Hospital massacre and the same day as the Bukit Chandu massacre ended. Today the factory is converted to a huge exhibition about the Battle of Singapore and the surrender. I didn’t have time to visit it on this trip, but it’s top of my list for my next return to Singapore.

It’s really hard to believe that my husband’s grandparents, and my great grandparents, literally lived through these events. Our ancestors wouldn’t recognise the Singapore of today – a wealthy, safe nation – our favourite country in the world.

My husband’s family don’t travel. They trace back for at least 300 years in the Cambridgeshire fens. Other than Percy, no-one we know of in his family has ever left Europe; most have never left England. It is with a deeper meaning that my husband fell in love with travel in Singapore, before knowing anything about his family history. We both feel a strong affinity to Singapore, and I’m now sure that it’s because those who came before us left pieces of themselves here for us to find.

May my great grandpa be looking down on me as I sit in Singapore Cathedral typing this in the church he called his.

And may Percy rest in peace.